Jennifer Champoux, "Creating the Book of Mormon Art Catalog: Why Religious Art Matters," Religious Educator 25, no. 1 (2024): 97–108.

Jennifer Champoux (bookofmormonart@gmail.com) is the director of the Book of Mormon Art Catalog.

As you explore the Book of Mormon Art Catalog, you will find images that transport your mind and heart to a higher plane. You will also find images that challenge your ideas and prompt you to reconsider familiar stories.

As you explore the Book of Mormon Art Catalog, you will find images that transport your mind and heart to a higher plane. You will also find images that challenge your ideas and prompt you to reconsider familiar stories.

Abstract: The Book of Mormon Art Catalog allows users to access and study a greater volume and variety of art based on this book of scripture than ever before. This open-access digital database includes more than four thousand images from seven hundred different artists hailing from fifty-five nations. The catalog provides a resource for teachers, enhances possibilities for scholarship, and creates new opportunities for artists. As an ongoing gathering of art, the catalog can also inspire new production, including scenes or approaches currently underrepresented in the art. Incorporating more art into our study and teaching of the Book of Mormon creates opportunities to be edified by the visual testimonies of artists and to discover opportunities for our own insights and revelations.

Keywords: Art, teaching the gospel, Book of Mormon

Thus, when—out of my delight in the beauty of the house of God—the loveliness of the many-colored gems has called me away from external cares, and worthy meditation has induced me to reflect, transferring that which is material to that which is immaterial, on the diversity of the sacred virtues: then it seems to me that I see myself dwelling, as it were, in some strange region of the universe which neither exists entirely in the slime of the earth nor entirely in the purity of Heaven; and that, by the grace of God, I can be transported from this inferior to that higher world in an analogical manner.

—Suger, Abbot of Saint-Denis[1]

Basking in the glow of the new stained-glass windows of his abbey church in 1140 CE, Abbot Suger understood the ability of art to transform the mundane. These art objects not only helped create a feeling of sacred space but also helped educate the laity. The largely illiterate French worshipers in this Parisian commune learned Bible stories by viewing the luminous panels. Around the same time, another French abbot named Bernard of Clairvaux was thinking and writing about art in his Cistercian monastery in the northeastern countryside. Unlike Suger, Clairvaux was troubled by what he saw as the distracting excesses of religious art. In his 1125 Apologia ad Guillelmum, Clairvaux expressed concern that viewing art might eclipse reading scripture and that patronizing the arts might come at the expense of caring for the poor.

Latter-day Saint Visual Culture

Strands of both lines of thought show up in the aesthetic theory and practice of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints today. The visual culture of the Church stands at the intersection of a desire for art that illustrates and uplifts and a concern that art can distract or even misinform. Leaders of the Church regularly commission, collect, and use much more art than other Restoration branches. Yet, they also prescribe boundaries for this art, including where it can be placed (e.g., classrooms and hallways are deemed appropriate places, but ordinance rooms or chapels generally are not) and which visuals are allowed (e.g., meetinghouse foyers can only have images that include Jesus Christ from an approved selection of foyer artwork).[2]

Despite some trepidation about the power of visuals, leaders of the Church have long encouraged members to illustrate scripture and to share their testimonies through art. In a 1976 Brigham Young University devotional, Elder Boyd K. Packer urged Latter-day Saints to bring their artistic talents to bear on religious matters. Packer acknowledged that “we are able to feel and learn very quickly through music, through art, through poetry some spiritual things that we would otherwise learn very slowly.”[3] For years Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf has lauded the God-given spark of creativity within each child of God.[4] In a 2021 message, Elder Uchtdorf said, “Art shows there is a greater purpose in life which transcends our daily worries, stresses, pleasures, and joys. Art can transmit a message of hope, light, and truth anchored in Jesus Christ, His glory, and His work for the eternal well-being of the whole human race.”[5] Similarly, Laura Paulsen Howe, the art curator for the Church History Museum, was recently quoted in a Church News article saying, “Art provides us a platform to work out who we are and what we think and what we feel, and so it becomes another way to come unto Christ.”[6]

Although official Church publications and manuals tend to return to a particular set of images, this canon of art has expanded slightly in recent years. Additionally, members of the Church around the world, perhaps heeding the words of Elder Uchtdorf and feeling motivated to express their own witnesses and experiences with scripture, are creating a multitude of artworks outside “official” lists.

Until now it has been difficult to gauge the volume of art inspired by the Book of Mormon. Scholars had no way to get a clear view of trends in Book of Mormon art. Members were limited in what they could find to aid their personal study and teaching. Many collections, including the Church History Museum full catalog, are not available to the public. Some art could only be found by searching out obscure publications. Artists outside the United States do not necessarily have the same channels to present their work to Church members around the world, making it more difficult to find their work.

Indexing Book of Mormon Art

The Book of Mormon Art Catalog, which launched in 2022, meets these challenges and is now the largest, most comprehensive collection of visual art based on Book of Mormon content. This digital database currently indexes more than four thousand artworks and is constantly growing. The site (https://

The idea for the book of Mormon Art Catalog came about as I was writing a history of visual depictions of Lehi’s dream.[8] I wanted to understand the various ways in which artists had responded to 1 Nephi 8. Without a central repository of art, I pulled information together from various sources including museum catalogs, private collections, artist studios, commercial galleries, books and articles, and the Church’s gospel media offerings. The more I looked the more I found, and the sheer volume of artworks on this single chapter surprised me.

I began to ask questions such as these: What was the earliest depiction of Lehi’s dream? How have artworks based on the dream changed over time? What patterns appear in the art? Are there differences in how artists from various countries illustrate the dream? Are there approaches to this scripture that are not visualized as much or at all? How does Lehi’s dream artwork production compare to artworks on other Book of Mormon passages?

This led me to broader questions about Latter-day Saint art: Which Book of Mormon scenes or figures are illustrated the most frequently and which have been largely overlooked? Which images have been used in Church media and publications, and has that affected subsequent art production? What is the ratio of female to male artists working on the Book of Mormon or being included in Church media? Without a comprehensive database, there was no way to responsibly investigate such questions.

What Is in the Catalog

The Book of Mormon Art Catalog includes all related art from the earliest piece in 1870 to new pieces being created today. The art comes from seven hundred different artists hailing from fifty-five nations. The artwork is done in a range of mediums including painting, drawing, print, film still, sculpture, textile, ceramic, carving, pottery, photography, mixed media, installation, and digital illustration. Some art is figurative and narrative, and some is abstract or more thematic. All of it exhibits an interest in and care for the Book of Mormon and the restored gospel.

These varied artistic approaches make for interesting comparisons. For instance, consider the ways in which images of Captain Moroni done by Lester Yocum and Julie Yuen Yim speak to you (figs. 1, 2). In some ways they are similar—both men appear as heroic bearded warriors with swords and armor, standing in front of the title of liberty. Both images visualize physical and spiritual strength. Both images move away from more traditional depictions of Moroni as Caucasian.[9] Yet, there are clear aesthetic and cultural differences.

Yocum, an artist from Utah, based his depiction on a young man his family knew. Moroni looks straight out at the viewer, calm but determined. The artist used oil paint to skillfully model the figure and create a sense of space, pulling the observer into the scene. Rather than showing Moroni as a battle-hardened veteran as he is in many other depictions, Yocum shows him as a young man on the brink of adulthood. The artist explains that he chose monochromatic shades of brown to symbolize the “earthiness” of Moroni.[10] With the dramatic angle of composition and strong pose of the figure, the image has an effect like an American war-movie poster.

Figure 1. Lester Yocum, Young Captain Moroni, 2004, oil on canvas, 36 x 40 inches.

Figure 1. Lester Yocum, Young Captain Moroni, 2004, oil on canvas, 36 x 40 inches.

Figure 2. Julie Yuen Yim, Captain Moroni, 2023, Chinese brush painting, 19 ½ x 23 ½ inches.

Figure 2. Julie Yuen Yim, Captain Moroni, 2023, Chinese brush painting, 19 ½ x 23 ½ inches.

Yim, who comes from Hong Kong, created her piece in a traditional Chinese brush painting style. The ancient military hero is reimagined as a colorful Chinese warrior. The two-dimensionality of the piece is heightened by the blank background, lack of shadows, outline of the figure, patterning on his armor, and calligraphy. The artist explains, “The guards of the gate is a type of painting that is pasted on the door at Chinese Lunar New Year . . . to ward off evil spirits.” Yim painted Moroni in this style because she admires his “faith, courage, and leadership in helping the Nephites in wars against their enemies, and [his] commitment and determination in maintaining peace.”[11]

Both portrayals of Captain Moroni show an eagerness on the part of the artists to engage deeply with the scripture. Yocum and Yim present novel ways to bring a familiar passage before our vision causing us, in turn, to rethink what we thought we knew. Picturing Moroni as a cinematic soldier or a Lunar New Year door guard enriches our understanding of his role by connecting him with broader traditions of heroism. Both paintings have the potential to make a figure that is often portrayed with Western features more relatable to certain members of the global Church.

Figure 4. Ben Crowder, Harrowed Up No More, 2023, digital illustration.

Figure 4. Ben Crowder, Harrowed Up No More, 2023, digital illustration.

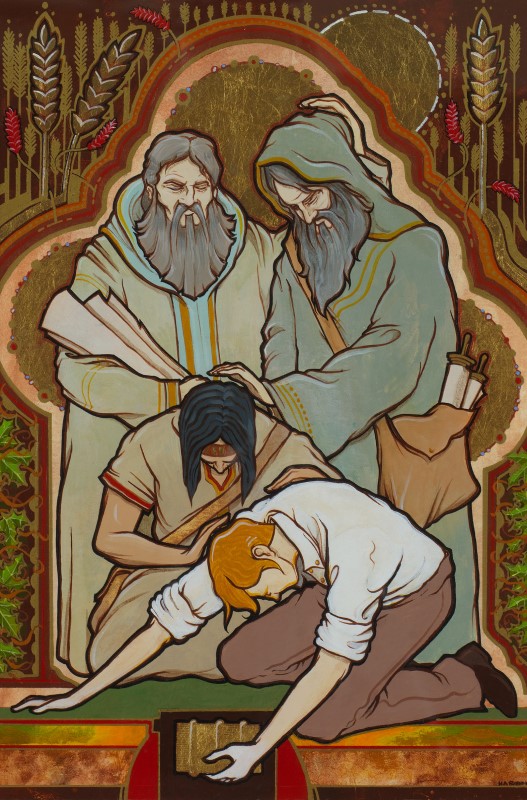

Differences in stylistic approach also encourage a reconsideration of scripture. Take, for example, two artworks based on Alma’s conversion: Robert T. Barrett’s Alma’s Fiery Conversion, and Ben Crowder’s Harrowed Up No More (figs. 3, 4). While most depictions of Mosiah 27 and Alma 36 focus on the dramatic appearance of an angel to Alma and the sons of Mosiah, these two paintings concentrate on the aftermath. Alma, alone now, reckons with his actions and chooses to follow Christ.

Barrett works in a figurative style and highlights the person of Alma. He includes exotic animal skins, hammered metal jewelry, Mesoamerican pottery, and stone architecture with Mayan-style carvings to lend a feeling of historicity. Barrett gives us a snapshot of an Ancient-American man. Crowder opts instead for an abstract minimalist approach. With a series of shapes and colors he relays the meaning of the scripture passage in a timeless way. Without the help of the title, which quotes Alma, the viewer has no way to know that this image applies specifically to Alma’s experience. In universalizing the themes, Crowder invites the viewer to consider how, through Christ, everyone can move from a state of rough, sinful fracture to a state of glorified, redeemed wholeness.

Both images are effective, although they work in quite different ways. They each help the viewer better understand or reassess a familiar story. One style may speak more to some people than others. The presentation of both artworks thus reaches a broader audience. What’s more, the comparison of the two images creates a rich dialogue and urges a depth of examination. The Book of Mormon Art Catalog allows for these kinds of rewarding comparisons by presenting a multitude of styles and approaches.

Figure 3. Robert T. Barrett, Alma’s Fiery Repentance, 1996, oil on board, 18 x 24 inches.

Figure 3. Robert T. Barrett, Alma’s Fiery Repentance, 1996, oil on board, 18 x 24 inches.

Using the Catalog for Study and Teaching

In the twelfth century, Bernard of Clairvaux worried about worshippers paying more attention to art than to scripture. In Latter-day Saint culture today, perhaps engaging more closely with art can help members dive deeper into the scriptures. Access to a greater volume and variety of visual art opens space for new interpretations and insights. Viewing more art encourages us to question our assumptions and to consider the choices made by artists, rather than taking images at face value. When we see Minerva Teichert’s depiction of Abinadi as a young man—rather than the very old man that he appears as in most images—we are compelled to turn back to Mosiah 11–17 and see what we are told about Abinadi (fig. 5). We might reflect on how Abinadi’s willing sacrifice of his life for the gospel as a young man might mean something different than as an elderly man. Art can, in fact, turn us back to scripture and help us read it more carefully.

Figure 5. Minerva Teichert (1888–1976), Trial of Abinadi, 1949–1951, oil on masonite, 36 x 48 inches. Brigham Young University Museum of Art, 1969.

Figure 5. Minerva Teichert (1888–1976), Trial of Abinadi, 1949–1951, oil on masonite, 36 x 48 inches. Brigham Young University Museum of Art, 1969.

Teachers can use the Book of Mormon Art Catalog to help students engage in this way. The former head of museum research at the BYU Museum of Art, Herman du Toit, noted, “Art has the capacity to create new meaning in the mind of the viewer, often by nondiscursive means.”[12] A teacher might ask students to look up a scripture chapter in the catalog and compare artworks found there. How do these artworks relate to each other and how do they relate to the scriptures they are based on? What might differences in the artistic portrayals tell us? Or a teacher might ask students to browse the catalog, find an artwork that is personally meaningful to them, and write a response explaining how the piece helped them consider doctrine or scripture in a new way.

Seminary teachers, Sunday School teachers, and parents can use images from the catalog to teach children the scriptures. My husband serves as an early-morning seminary teacher in our stake, and he uses the Book of Mormon Art Catalog to find images to enhance his lessons. At the start of this year, he showed several depictions of Lehi’s vision of the pillar of fire on a rock as recounted in 1 Nephi 1. This is not a moment that is illustrated much in Church manuals and resources. When the students saw J. Kirk Richards’s A Pillar of Fire, it helped bring the passage to life for them (fig. 6). The art allowed the students to visualize and consider these scriptures in a fuller way.

Figure 6. J. Kirk Richards, A Pillar of Fire, 2023, oil and acrylic on panel, 8 x 8 inches.

Figure 6. J. Kirk Richards, A Pillar of Fire, 2023, oil and acrylic on panel, 8 x 8 inches.

As an educational resource, the catalog website uses copyrighted content in accordance with Section 107 of the US Copyright Act. The information and images presented on the website are for teaching, scholarship, education, and research. The Book of Mormon Art Catalog does not sell artwork or licensing rights and does not receive revenue from the website. All images are protected by copyright—often the copyright holder is the artist, but in some cases it is another individual or institution. When possible, copyright information is included with the particular artwork. Where noted, many images presented on the website are used by permission of the copyright owner, and a few of the images are in the public domain. Images are intended for noncommercial use. It is the user’s obligation to consider and comply with copyright restrictions. Images on the site may not be used commercially or in publications without the written permission of the copyright holder. When using images, citing the Book of Mormon Art Catalog as the source is appropriate and appreciated.

Art and Revelation

A few years ago, President Henry B. Eyring exhibited some of the hundreds of watercolor paintings he has created over his lifetime. President Eyring said, “My motivation in all of my varied creative work seems to have been a feeling of love. . . . I felt the love of a Creator who expects His children to become like Him—to create and to build. In addition, I have always had a feeling of love for my family, friends, and others who might gain some satisfaction and joy from my efforts. So, my hope . . . is that those who see this exhibit might feel both the Savior’s and my own love for them.”[13] The Book of Mormon Art Catalog indexes these kinds of acts of love from hundreds of believers.

The Book of Mormon Art Catalog allows members of the Church to use a greater variety of visual sources for devotional and teaching purposes, enhances possibilities for scholarship on Latter-day Saint visual culture, and creates new opportunities for artists to reach a broader audience. This ongoing gathering of art can also help inspire new artistic production, including scenes or figures or approaches currently underrepresented in the art.

As Abbot Suger knew with his stained-glass Bible scenes nine hundred years ago, visualizing scripture makes it more memorable. But the flip side of this wonderful power of art is that when we are repeatedly exposed to only a handful of images our perception can be constrained by what we have seen. This is why a variety of religious art is so vital. It allows us to consider multiple perspectives, interpretations, and possibilities. Variety in Book of Mormon art, especially that which features a diversity of cultures and styles, also creates more opportunities for connection and inclusion in the global Church.

The Book of Mormon testifies of the spiritual power of revelation and the participatory nature of reading scripture. Incorporating more art into our study and teaching of the Book of Mormon ties into this process of revelation. We can be edified by the visual testimonies of artists, and we can, through the art, discover opportunities for our own insights and revelations.

As you explore the Book of Mormon Art Catalog, you will find images that transport your mind and heart to a higher plane. You will also find images that challenge your ideas and prompt you to reconsider familiar stories. Ultimately, in these thousands of artworks, you will find individuals wrestling with scripture and seeking God. In taking the time to carefully look ourselves, we can also be taught by the Spirit and come closer to the Savior.

Notes

[1] Suger, On the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and Its Art Treasures, ed. and trans. by Erwin Panofsky and Gerda Panofsky-Soergel (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979), 63–65.

[2] “Reverence for the Savior in our Meetinghouses,” Letter from the First Presidency, May 11, 2020.

[3] Boyd K. Packer, “The Arts and the Spirit of the Lord,” Brigham Young University devotional, February 1, 1976, https://

[4] See President Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “Happiness, Your Heritage,” in Conference Report, October 2008, https://

[5] Dieter F. Uchtdorf, Facebook, November 8, 2021, https://

[6] Sydney Walker, “Express Faith in Jesus Christ Through Art; Enter Church History Museum’s 12th International Art Competition,” Church News, August 17, 2020, https://

[7] This support also enabled me to hire several outstanding BYU student research assistants: Noelle Baer, Emma Belnap, Candace Brown, Elizabeth Finlayson, Aliza Keller, Lucy Lacanienta, and Grace Truett.

[8] See Jennifer Champoux, “The Thing Which I Have Seen: A History of Lehi’s Dream in Visual Art,” in Approaching the Tree: Interpreting 1 Nephi 8, ed. Benjamin Keogh, Joseph M. Spencer, and Jennifer Champoux (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University, 2023).

[9] See, for example, Friberg, Arnold, Captain Moroni Raises the Title of Liberty, 1952–55, https://

[10] Lester Yocum, “Lester Yocum with his ‘Young Captain Moroni,’” YouTube, uploaded by Book of Mormon Art Catalog, February 21, 2023, https://

[11] Julie Yuen Yim, Instagram, August 4, 2023, https://

[12] Herman du Toit, “Preface,” in Art and Spirituality: The Visual Culture of Christian Faith, ed. Herman du Toit and Doris R. Dant (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2008), xi–xiii.

[13] Marianne Holman Prescott, “BYU–Idaho Displays President Eyring’s Artwork,” Church News, September 27, 2017, https://